Chapter 4. Rural Household Characteristics and Perspectives

Mamoru Sawada, Mitsuyoshi Ando and Leonard Apedaile

The logical framework

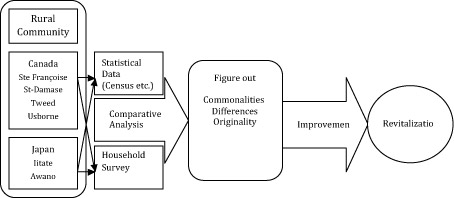

Rural revitalization begins with decisions taken in rural households. Perceptions by households of how they relate to their communities and how their communities relate to them in terms of social capital are important influences on their vitality. This chapter addresses those perceptions based on evidence from the comparative study of rural households in Japan and Canada. A logical framework was used to reveal commonalities, differences and originalities, which could inform revitalization strategies (see Figure 1).

The results of the household surveys uncover as much variability among the sites within each country as between the two countries. The demographics of depopulation, confidence in political leadership and birth roots appear to be slow changing attributes of households unlikely to change in response to short term initiative or stimulus aimed at revitalization.

Interpretation of the survey results raises the question of whether the vitality of rural households performs mainly a stabilizing function rather than propel growth of the household economy for development. Stabilization is interpreted as the outcome of household risk management strategies, including the whole range of options between subsistence and entrepreneurial activities in both the formal and informal economies.

Table 1 summarizes the comparative biographic statistics for the Japanese and Canadian sites and changes over the past decade. The Japanese sites have much higher populations than the Canadian sites. Awano is the site with the largest population with over 10,000 people in 2000, whereas Ste Françoise, the site with the lowest population, had less than 500 people. Population decreases are typical. Between 19911996 and 19962001, Japan’s Iitate tops the list. Population shrinkage in that town has been rapid with numbers falling by 827 between 1990 and 2000.

Table 1: Biographic profiles for selected rural sites in Canada and Japan, 1990-2001

| Site Name | Ste Françoise | St-Damase | Tweed | Usborne | Iitate | Awano |

| Nation Province / Prefecture |

Canada Quebec |

Canada Quebec |

Canada Ontario |

Canada Ontario |

Japan Fukushima |

Japan Tochigi |

| Population | ||||||

| 1990/91 | 506 | 1,348 | 1,626 | 1,552 | 7,920 | 11,065 |

| 1995/96 | 467(-8) | 1,362(1) | 1,572(-3) | 1,535(-1) | 7,586(-4) | 10,966(-1) |

| 2000/01 | 453(-3) | 1,327(-3) | 1,539(-2) | 1,490(-3) | 7,093(-6) | 10,636(-3) |

| Percentage of population 65 years or older (%) | ||||||

| 1995/96 | 22.3 | 11.0 | 23.2 | 11.7 | 25.2 | 26.4 |

| 2000/01 | 24.2 | 12.0 | 20.8 | 12.8 | 30.2 | 28.6 |

| Percentage of population by economic sector (2000/01) (%) | ||||||

| Primary | 31.6 | 5.8 | 3.4 | 31.6 | 31.8 | 14.6 |

| Secondary | 23.7 | 48.1 | 16.0 | 20.3 | 42.7 | 42.7 |

| Tertiary | 44.7 | 46.2 | 79.0 | 49.7 | 25.5 | 42.6 |

| Labour force participation ratio (%) (Note 1) | ||||||

| 1995/96 | 50 | 60.5 | 57.1 | 69.2 | 66.1 | 64.1 |

| 2000/01 | 50 | 73.6 | 46.7 | 72.5 | 63.6 | 61.8 |

| Unemployment ratio (%) | ||||||

| 1995/96 | 7.5 | 8.7 | 16.9 | 3.7 | 1.6 | 2.5 |

| 2000/01 | 25.6 | 5.8 | 8.3 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| Number of households (2000/01) | 140 | 395 | 455 | 425 | 1,757 | 2,894 |

| Household size (2000/01) | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 3.7 |

| No. of respondents | 90 | 130 | 96 | 94 | 197 | 199 |

Source. Japan Bureau of the Census, Household Survey.

Note 1. The labour force participation ratio calculated by Census Japan is the percentage of persons 15 years or older who are engaged in any kind of job for a day or more in the week before the Census.

One aspect of this decline is the high ratio of people 65 years or older, 28-30% in the Japanese sites. The two Canadian sites of Ste Françoise and Tweed are also aging with 20-24%, but St-Damase and Usborne are younger with 11-13%.

Economic diversification in the sites varied considerably in terms of the population employed by the primary sector, including agriculture. Less than 5% of the population in St-Damase and Tweed in Canada are employed in the primary sector, whereas in Usborne and Ste Françoise it reaches close to 30%. In Japan on the other hand, those figures are 32% for Iitate and no more than 15% for Awano where close to 85% are employed in secondary and tertiary industries.

A long-standing issue in Canada and more recently in rural Japan has been high unemployment rates (see Table 2 and Figure 2). The Canadian sites have higher unemployment rates, notwithstanding differing methods of measurement. Ste Françoise had an unemployment rate of 7.5% in 1996, but by 2001 it had ballooned to 25.6%.

Table 2. Participation rate and unemployment rate at each site

| 1996 | 2001 | Change from previous year | ||

| Ste Françoise | participation rate (%) | 50 | 50 | 0.0 |

| unemployment rate (%) | 7.5 | 25.6 | 18.1 | |

| St-Damase | participation rate (%) | 60.5 | 73.6 | 13.1 |

| unemployment rate (%) | 8.7 | 5.8 | -2.9 | |

| Tweed | participation rate (%) | 57.1 | 46.7 | -10.4 |

| unemployment rate (%) | 16.9 | 8.3 | -8.6 | |

| Usborne | participation rate (%) | 69.2 | 72.5 | 3.3 |

| unemployment rate (%) | 3.7 | 1.7 | -2.0 | |

| Iitate | participation rate (%) | 66.1 | 63.6 | -2.5 |

| unemployment rate (%) | 1.6 | 2.4 | 0.8 | |

| Awano | participation rate (%) | 64.1 | 61.8 | -2.2 |

| unemployment rate (%) | 2.5 | 2.6 | 0.1 |

Source. Bureau of the Census and Population Census of Japan

However, in Tweed and St-Damase, the unemployment rate fell between 1996 and 2001 to a level of 5.8% in St-Damase and 8.3% in Tweed. Unemployment rates are lower for the two Japanese sites than for three of the four Canadian sites, with Usborne the exception. Nevertheless, unemployment has become a major social issue with only a slight increase in unemployment in both Iitate and Awano over the period from 1995 to 2000.

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the changes in unemployment rates in Iitate and Awano between 1990 and 1995 and to 2000. A trend common to both Iitate and Awano is that unemployment is worsening among younger age groups, while labour force participation rates are moderate and steady. In Iitate in particular, unemployment is climbing among all age groups below 40. Unemployment among the younger population is having a serious impact on households, including 1519 year olds for whom that rate is worsening remarkably. The data may be interpreted to suggest that the situation is even worse for younger people. The participation rate may be being held steady by delayed retirement of older people while participation by younger people declines with out-migration. The two age comparable sites of Tweed and Ste Françoise in Canada have much lower participation ratios because their older people do retire.

Source. Population Census of Japan

Source. Population Census of Japan

Source. Population Census of Japan

Now let us take a look at household incomes. An exchange rate of 100 yen per Canadian dollar was used for an easy comparison across sites at the time of the survey. Incomes of households differ substantially among the Canadian sites. The percentage of low-income earners is high in Tweed and Ste Françoise, with over 60% of respondents earning less than $40,000 per year. On the other hand, in Usborne and St-Damase that percentage is lower at about 25% and just under 40% respectively. Half or more of the households earn $40,000 or more in areas within Iitate and Awano where the municipal administration believes progress is being made in revitalization.

Areas of the town or village designated by municipal representatives as “areas being revitalized” had generally larger proportions of the households with higher incomes. These incomes contrast sharply with the incomes of households in areas where revitalization is not taking place. Half or more of the respondents’ households earn less than $40,000 in parts of Awano where revitalization is not taking place. Thus, in the Japanese sites, differences in income exist among areas within the same town. It may be inferred that there is some relationship between revitalization and household income.

The impact of lower participation rates and higher unemployment rates for the under 40 population also shows up in widening rural urban income differentials (see Figure 5). Using 100 as the index of national average income for the period 1997 to 2001, income in cities held steady at a level of 100110. However, the trend in Iitate since 1997 is to lower income levels, increasing the income disparity with cities through 2001. The differential between Awano and Iitate income levels also expanded, albeit only slightly, from 1997 onwards. In other words, from the 1990s onwards the differential with cities has expanded as a result of local economic stagnation and the deterioration of employment conditions in the purely rural Iitate economy. This widening of the rural urban income gap is clear evidence of relative devitalization in Iitate during the period leading up to the household survey.

Source. Minryoku 2002, Asahi Shinbun.

The blend of born-in-place residents and newcomers will be seen later as a factor associated with perceptions about the communities to which households belong. Newcomers are people who live in the sites but were not born there. This blend is another difference in the biographic features of the Japanese and Canadian sites (see Table 3). Sixty-six percent of Iitate respondents were born in that village, and in Awano that figure was 55%, whereas in the Canadian sites, that percentage was generally lower, in Ste Françoise 51%, St Damase 48%, Usborne 47%, and in Tweed only 19%. However, looking at the percentage of those who had never moved out of their respective towns, the figure for Tweed was only 9%. The percentage of respondents in the Japanese sites whose family had settled in the town 200 years or more prior to 2001 was as high as 19%. This question was not asked in Canada. However, in terms of the percentage of current rural community residents who themselves had settled in their respective communities, there was little difference between the Japan and Canada sites.

Table 3. Demographic shifts among the respondents at each site

| Born in community | Percent (%) | Lived all life in community | Percent (%) | Born in other community | Percent (%) | Total | |

| Ste Françoise | 46 | 51 | 30 | 33 | 44 | 49 | 90 |

| St-Damase | 62 | 48 | 44 | 34 | 68 | 52 | 130 |

| Tweed | 18 | 19 | 9 | 9 | 78 | 81 | 96 |

| Usborne | 44 | 47 | 37 | 39 | 50 | 53 | 94 |

| Iitate | 124 | 66 | 68 | 36 | 63 | 34 | 187 |

| Awano | 104 | 55 | 59 | 31 | 84 | 45 | 188 |

Source. Household Survey

Community Perceptions of 'Openness'

The questionnaire asked respondents to assess their communities according to eight qualities or attributes listed below. Scores was assigned for five possible responses to a statement that described each of the eight perceived qualities as follows: “Strongly disagree”, 1 point; “disagree”, 2 points; “neutral”, 3 points; “agree”, 4 points; “strongly agree”, 5 points. A comparative analysis was then conducted on the average values of the responses for each site.

The statements in the questionnaire to test perceptions of ‘openness’ (here = in community) include:

- People here are open to opinions that are very different from their own

- People here are willing to contribute time and money for community projects

- People here work together for the good of the community

- Women have opportunities for leadership positions here

- People living here are willing to accept people from different race and ethnic groups

- Young adults (under the age of 35) have opportunities for leadership positions here

- People here are helped by people from outside

- People here are friendly with outsiders

This part of the household questionnaire was designed so that agreement with each of the eight statements about the community is interpreted as a positive opinion about the community. The average scores for all classifications of respondents over all eight attributes were greater than 3.00 signifying a generally positive perception by respondents of the site in which they live. The focus of the analysis was on patterns of perceptions from the perspective of insight into revitalization strategies. Differences between the Canadian and Japanese sites were tested for significance using a t-test and confidence levels of 1% and 5%. Test results and average scores are reported in Table 4.

Respondents in Japan often tended to more “neutral” responses than their Canadian counterparts. Therefore it would seem that the differences between the averages for Japan and Canada may have been less about different opinions than about noncommittal responses in Japan. The notable exceptions are the two statements about tolerance, which many in either country would perhaps find particular difficulty denying as fundamental aspects of their communities’ value systems. This result could also reflect an unconscious cultural bias in the statements used to test perceptions, yet not picked up in the pretest.

Setting aside possible methodological reasons for the tendency to noncommittal responses in Japan, differences were identified. The first observed factor is age. Two age-related patterns were revealed. These patterns were common to both Japan and Canada. People of age 50 or older in both countries agreed that rural communities are “open to opinions that are different”, whereas younger people under 50 perceived that rural communities are on average neutral on the question. Secondly, people of age 50 or older in Japan agreed that residents of their community are “willing to contribute time and money for community projects”, whereas the younger age group showed neutral perceptions. Both age groups in Canada agreed with this statement, with a significantly higher score for the older Canadian respondents.

The second observation is that income levels in the Canadian sites were not associated with response patterns for any of the eight attributes. It was not possible to identify any significant difference for any of the eight items between those earning $40,000 (4 million yen) or more and those earning less than $40,000. The same absence of an incomes effect applied to response patterns for six of the eight attributes in Japan. The exceptions were the responses to the statements “helped by people from outside” and “People here friendly with outsiders”. For each of these attributes, those earning more than 4 million yen ($40,000) tended to agree more strongly with this statement of openness. The overall scores mean that rural/urban friendships and mutual aid are seen as useful strategic moves for rural households at all income levels for sites in both countries.

The third observation is that being born within the community where people currently reside is the factor associated with the most significant differences between Japan and Canada. Responses were grouped for people born in the community in which they currently live and those born elsewhere. For the Japanese sites, no significant differences were observed for any of the eight items. In Canada on the other hand, significant differences at the 95% and 99% levels of confidence were found for all eight items. The assessment of community perceptions in the four Canadian sites clearly differs according to whether or not the person was born there. Those born in a community generally were in stronger agreement with a positive perception for each of the attributes and had a higher opinion of their community than those born elsewhere. The most interesting result is that the younger group of Canadian respondents averaged a neutral score of 3.01 for their perception that their community was open to different opinions. On all other attributes, their scores were somewhat to quite positive. Evidence for the two Japanese sites suggests that being born in a community did not influence perceptions. However some scores for both groups approached neutrality especially on contributions of time and money and help by people from outside the community.

These results are very interesting and may be interpreted in several ways. In Canada, the decision to move outside the community is an individual decision. Household members have a choice to stay or migrate with minimal to no social sanction to leaving home, especially for younger people. As a result it may be inferred that those born in the place who have a poor opinion of a community will have already moved out leaving behind those with a better perception of the community. Conversely in Japan, individual choice is limited by social norms with respect to changing residence. Even if the opinion of a community is low it is not easy to move without reflecting on the family. Consequently a rural community may contain individuals locked in by social norms making them even more negative than they might otherwise be if they could move.

The most useful interpretation concerns the reasons for newcomers to choose to move into a community. In Canada, people migrate for jobs, lifestyle and a wide range of opportunities, or to get away from an unsatisfactory situation. Only a modest proportion would be expected to have close family ties or to move in through marriage as is the case in Japan. Japanese have traditionally moved among rural places primarily as spouses. They are likely to be accepted into the community socially and through assimilation to adopt their new family’s perceptions of the community.

Table 4. The difference of the average about the assessment of the communities

| Nation | Age | Income | ||||||||||

| Japan | Canada | Japan | Canada | Japan | Canada | |||||||

| <50 | 50+ | <50 | 50+ | under 40 Mill¥ |

over 40 Mill¥ |

under $40,000 |

over $40,000 |

|||||

| 1 | Open to opinion that are different | 3.23 | 3.20 | 3.09 | 3.35** | 3.01 | 3.34** | 3.15 | 3.33 | 3.18 | 3.26 | |

| 2 | Contribute time and money for projects | 3.17 | 3.97 ** |

3.05 | 3.26 * |

3.82 | 4.08 ** |

3.09 | 3.24 | 4.03 | 3.88 | |

| 3 | Work together for good of community | 3.69 | 3.94 ** |

3.69 | 3.68 | 3.88 | 3.98 | 3.65 | 3.73 | 3.97 | 3.85 | |

| 4 | Women have leadership opportunities | 3.53 | 3.83 ** |

3.49 | 3.58 | 3.74 | 3.89 | 3.53 | 3.56 | 3.81 | 3.88 | |

| 5 | Accept people of different race/ethnicity | 3.46 | 3.46 | 3.54 | 3.39 | 3.34 | 3.54 | 3.47 | 3.43 | 3.47 | 3.55 | |

| 6 | Young adults have leadership opportunities | 3.19 | 3.42 ** |

3.22 | 3.16 | 3.40 | 3.44 | 3.19 | 3.20 | 3.40 | 3.39 | |

| 7 | Helped by people outside | 3.20 | 3.34 * |

3.21 | 3.19 | 3.36 | 3.34 | 3.11 * |

3.32 | 3.33 | 3.38 | |

| 8 | Friendly with outsiders | 3.61 | 4.00 ** |

3.54 | 3.66 | 3.95 | 4.03 | 3.54 ** |

3.76 | 3.98 | 4.03 | |

| Sex | Location | Agri-Industry | Province | |||||||||

| Japan | Canada | Japan | Canada | Canada | ||||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Awano | Iitate | Usborne Ste.Françio |

Tweed St-Damase |

Quebec | Ontario | |||

| 1 | Open to opinion that are different | 3.29 | 3.18 | 3.17 | 3.26 | 3.18 | 3.28 | 3.18 | 3.22 | 3.31 | 3.07 * |

|

| 2 | Contribute time and money for projects | 3.23 | 3.11 | 3.98 | 3.96 | 3.18 | 3.15 | 3.83 | 4.10 ** |

3.89 | 4.07 * |

|

| 3 | Work together for good of community | 3.74 | 3.64 | 3.95 | 3.91 | 3.68 | 3.70 | 3.78 | 4.07 ** |

3.85 | 4.04 * |

|

| 4 | Women have leadership opportunities | 3.50 | 3.56 | 3.81 | 3.87 | 3.24 | 3.79 ** |

3.87 | 3.80 | 3.81 | 3.86 | |

| 5 | Accept people of different race/ethnicity | 3.54 | 3.38 | 3.39 | 3.60 * |

3.25 | 3.63 ** |

3.56 | 3.39 | 3.49 | 3.43 | |

| 6 | Young adults have leadership opportunities | 3.19 | 3.18 | 3.36 | 3.53 | 2.94 | 3.39 ** |

3.44 | 3.41 | 3.54 | 3.29 * |

|

| 7 | Helped by people outside | 3.19 | 3.21 | 3.33 | 3.37 | 3.23 | 3.18 | 3.43 | 3.26 | 3.37 | 3.32 | |

| 8 | Friendly with outsiders | 3.65 | 3.58 | 4.01 | 3.98 | 3.54 | 3.67 | 3.39 | 4.05 | 4.06 | 3.94 | |

| Birth place | ||||||||||||

| Japan | Canada | |||||||||||

| In | Out | In | Out | |||||||||

| 1 | Open to opinion that are different | 3.24 | 3.22 | 3.47 | 3.01 ** |

|||||||

| 2 | Contribute time and money for projects | 3.19 | 3.09 | 4.07 | 3.90 * |

|||||||

| 3 | Work together for good of community | 3.75 | 3.59 | 4.05 | 3.86 * |

|||||||

| 4 | Women have leadership opportunities | 3.59 | 3.41 | 3.96 | 3.74 ** |

|||||||

| 5 | Accept people of different race/ethnicity | 3.40 | 3.57 | 3.67 | 3.32 ** |

|||||||

| 6 | Young adults have leadership opportunities | 3.24 | 3.11 | 3.60 | 3.29 ** |

|||||||

| 7 | Helped by people outside | 3.20 | 3.19 | 3.52 | 3.20 ** |

|||||||

| 8 | Friendly with outsiders | 3.61 | 3.62 | 4.10 | 3.92 * |

|||||||

Source. Household Survey.

*Less than 5%

**Less than 1%

The fourth pattern pertains to the economic diversification of the sites. Respondents in Iitate and at Awano assessed their communities differently, though generally positively, for three of the eight attributes, including: “women have leadership opportunities”, we “accept people of different race/ethnicity”, and “young adults have leadership opportunities”. The differences, however, do not seem to be associated with the diversification attribute and, in fact, are counter-intuitive. Iitate showed generally more positive perceptions for these three attributes than respondents in Awano. Note that the Awano economy is more diversified than the Iitate economy according to employment by sector. These qualities of a community relate to the position of women and youth in the governance and leadership in the rural communities. This result may be evidence of the success of more than a decade of support measures in Iitate for engaging women and youth in the development of the municipality, such as sending females from the community on overseas tours, in order to enhance the voice of women in the community. It would seem, in the absence of such initiatives, that economic diversification in itself does not perform an emancipation function.

The Canadian comparison grouped the relatively agrarian sites of Usborne and Ste Françoise with a large proportion of the population in primary industries, for a comparison with Tweed and St-Damase combined with smaller proportions of their populations in primary industries. Significant differences in two of the perceptions of the eight attributes were found. These were “contribute time and money for projects” and “work together for the good of community”, indicators chosen by design to reveal the strength of ties within the community. The sites characterized by greater economic diversification away from agriculture demonstrated stronger internal ties. No patterns of perceptions could be distinguished between male and female respondents in either country’s sites.

Revitalization strategy

Consider now each of the eight attributes in terms of revitalization strategy.

For revitalization to take place, it is thought that people should be more open to different opinions and contribute time and money for community projects. The evidence suggests that these attributes are associated with older age groups, economic diversification and place of birth. People in all six sites in Canada and Japan think revitalization is necessary for their community, but people of age 50 or older averaged higher scores than the younger group. In fact the younger group in both countries had neutral scores for perceptions of openness to different opinions, as did Canadian respondents born outside the community.

A neutral average score was also observed for people born outside their community in Japan for perceptions that the community is giving of its time and money. Do the younger people and those born outside their community observe the real nature of their community better than the older people or vice versa? Both groups agree the community needs to be revitalized, but the younger group does not feel that their views are taken into account in these research sites. A revitalization strategy for all sites could target the relationships between older long time residents and younger newcomers for communication, inclusion in decision making and volunteering time and money.

Working together for the good of the community is seen as an indicator of social cohesion. Canadian respondents, especially those born in their site and in economically diversified sites and in Quebec, appear to perceive their communities as pulling together for the common good, more so than do their Japanese counterparts. The patterns of responses did not vary by age, incomes, or gender. These matters are extremely complex and systemic, making interpretation difficult in terms of revitalization strategy. The primary sector in Canada is characterized by individualism. However, both the ‘Union des Producteurs Agricoles’ (farmers union) and Solidarite Rural (rural lobby) in Quebec have invested in leadership for decades to build a common rural identity based on belonging to the common cause of rural grievance and social and economic merit. Consequently, these results seem to confirm the idea that rural revitalization is a very long term process, and therefore likely to be vulnerable to political discord, volunteer succession practices and burnout for leaders.

The perception of a community as being a place where women have leadership opportunities shows up in Canada and in Iitate in Japan. This perception cuts across incomes, age, gender and economic diversification in Canada and is strong among respondents born in their community. Revitalization viewed in terms of mobilizing resources could benefit from tapping into the underutilized capabilities of women and the resources they control or influence in households. As this may be a matter of entitlement, mobilizing female leadership seems also to fall into the category of long term investment in revitalization.

Acceptance of people with a different racial or ethnic background is generally universal across all sites in Japan and Canada, but shows up more strongly in Iitate and in Canada among women and people born within their site. For several years, the Municipality of Iitate sent women on overseas tours, suggesting that affirmative action to broaden women’s perspectives of opportunity could be a successful part of a revitalization strategy.

The perception that young adults have leadership opportunities shows up among Canadian respondents and in Iitate, but not among Canadians not born in their community. The involvement of youth is a mobilization issue. Canadian rural youth out-migration is a feature of rural aging. The individualism of Canadians around the matter of exercising choice suggests that having leadership opportunities is only part of the story. Exercising these opportunities is an unresolved challenge for revitalization.

The perception that people are helped by others from outside the site has been interpreted earlier in terms of a safety net for low income households. Canadians born in their site agree with this perception whereas those not born there disagree. Those born in their rural site are in a sense a residual after years of selective out-migration. These results do not reveal an age pattern in this help from outside, suggesting that those born in the site cross the age spectrum of rural poverty.

Finally, the perception that a community is friendly towards outsiders is meant to indicate the presence of bridging social capital. Canadian respondents on average share this perception. However among Japanese respondents, only the higher annual income group (over 4 million Yen) tends to share this perception while the lower income group does not. This result for Japan suggests a distinction between relationships with people outside the community and relationships that are associated with help or safety nets. The Canadian results do not suggest this distinction or any other pattern relating to age, economic diversification or gender.

Bridging social capital is theoretically a valuable asset in the revitalization process. It appears to be present in Japanese sites for the upper income groups, which presumably include the entrepreneurial class. In the Canadian sites this asset is perceived by people born and raised in the community but not by newcomers. This suggests that newcomers in the Canadian sites may have moved to a rural place to escape competition in business and commerce or to seek refuge from a difficult social or employment situation or because of a unique need for closeness to nature or isolation from other humans. Their potential as contributors to revitalization likely cannot be achieved through bridging social capital. Higher income rural Japanese, however, could be a strategic force in revitalization, despite not being perceived as contributing time and money to the common interest of their community. Their main contribution could be through private investment and job creation.

Assessment of leadership and governance in the Community

In both Japan and Canada, national and regional governments perform a variety of functions and are major players in the rural economy. Respondents were asked to assess the perceived effectiveness of contributions made to the revitalization of the community by six players in rural governance and leadership (see Table 5). The six players were the mayor, municipal councillors, local business leaders, elected provincial/prefectural representatives, elected national/federal representatives, and community or voluntary groups. A numerical score was applied to each as follows: Very ineffective, 1 point; Ineffective, 2 points; Neutral, 3 points; Effective, 4 points; and Very effective, 5 points. The average scores for the responses were compared, again using the large sample t-test.

For all sites and all groupings of respondents only the mayor and volunteer groups were universally perceived to be the most effective agents for development in communities with scores above 4.00. The only assessment for which no significant differences in average scores for the Japanese and Canadian groups of sites was for the effectiveness of the mayor, as agreed to be effective. There were significant differences for the perceived effectiveness of each of the other five players. In both countries the scores for the difference in average values were negative for all five players, indicating that the scores given by Canadian respondents were higher than those given by Japanese. The inference is that in Canada respondents are in agreement that the five players are effective contributors to rural success.

Perceptions of effectiveness for some players vary by age of the respondent in both Japan and Canada. The scores given by the higher age group were higher for elected provincial/prefectural representatives. The same pattern is observed for Diet members /members of Parliament except that the Japanese respondents generally perceive their Diet members to be ineffective with scores under 3.00. Respondents under 50 gave lower scores for effectiveness. The reason for that pattern in the Japan sites may be that the respondents hold the long ruling Liberal Democratic Party responsible for the general deterioration of the economic and social environment for younger generations of rural people illustrated by the worsening unemployment rates in Awano and Iitate noted earlier. The assessment of effectiveness by Iitate respondents generally was lower compared to that in Awano, suggesting intuitively that the worsening socio-economic conditions for Iitate, such as the rising unemployment rate for young people, are blamed on the national government. Local politicians seem not to be held responsible for economic conditions in the Japan sites.

Table 5. The differences of the averages about the assessment of administrative entities

| Nation | Age | Income | ||||||||||

| Japan | Canada | Japan | Canada | Japan | Canada | |||||||

| <50 | 50+ | <50 | 50+ | under 40 Mill¥ |

over 40 Mill¥ |

under $40,000 |

over $40,000 |

|||||

| 1 | Mayor effective | 4.08 | 4.07 | 3.99 | 4.16 | 4.01 | 4.11 | 4.09 | 4.06 | 4.13 | 3.96 | |

| 2 | Councilors effective | 3.48 | 3.87 ** |

3.43 | 3.53 | 3.78 | 3.92 | 3.49 | 3.46 | 3.90 | 3.76 | |

| 3 | Businesses effective | 3.35 | 3.90 ** |

3.38 | 3.33 | 3.97 | 3.86 | 3.38 | 3.30 | 3.92 | 3.85 | |

| 4 | Provincial elected effetive | 3.28 | 3.44 * |

3.13 | 3.40 ** |

3.21 | 3.60 ** |

3.23 | 3.30 | 3.42 | 3.52 | |

| 5 | Federal elected effective | 2.61 | 3.37 ** |

2.45 | 2.73 ** |

3.17 | 3.50 ** |

2.57 | 2.65 | 3.35 | 3.43 | |

| 6 | Voluntary groups effective | 3.75 | 4.30 ** |

3.78 | 3.72 | 4.25 | 4.33 | 3.77 | 3.74 | 4.35 * |

4.18 | |

| Sex | Location | Agri-Industry | Province | |||||||||

| Japan | Canada | Japan | Canada | Canada | ||||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Awano | Iitate | Usborne Ste.Françio |

Tweed St-Damase |

Quebec | Ontario | |||

| 1 | Mayor effective | 4.23 | 3.94 ** |

4.03 | 4.15 | 4.00 | 4.16 | 4.01 | 4.13 | 4.06 | 4.09 | |

| 2 | Councilors effective | 3.61 | 3.36 * |

3.88 | 3.85 | 3.50 | 3.47 | 3.71 | 4.00 ** |

3.97 | 3.74 * |

|

| 3 | Businesses effective | 3.48 | 3.22 ** |

3.94 | 3.83 | 3.35 | 3.35 | 3.96 | 3.86 | 4.08 | 3.71 ** |

|

| 4 | Provincial elected effetive | 3.40 | 3.17 * |

3.42 | 3.48 | 3.51 | 3.05 ** |

3.38 | 3.50 | 3.21 | 3.68 ** |

|

| 5 | Federal elected effective | 2.68 | 2.53 | 3.30 | 3.47 | 2.73 | 2.49 * |

3.64 | 3.11 ** |

3.13 | 3.61 ** |

|

| 6 | Voluntary groups effective | 3.77 | 3.75 | 4.36 | 4.18 * |

3.79 | 3.71 | 4.11 | 4.45 ** |

4.23 | 4.37 | |

| Birth place | ||||||||||||

| Japan | Canada | |||||||||||

| In | Out | In | Out | |||||||||

| 1 | Mayor effective | 4.07 | 4.08 | 4.16 | 4.00 | |||||||

| 2 | Councilors effective | 3.45 | 3.53 | 4.01 | 3.75 ** |

|||||||

| 3 | Businesses effective | 3.30 | 3.44 | 4.05 | 3.79 ** |

|||||||

| 4 | Provincial elected effetive | 3.26 | 3.27 | 3.49 | 3.41 | |||||||

| 5 | Federal elected effective | 2.64 | 2.56 | 3.56 | 3.23 ** |

|||||||

| 6 | Voluntary groups effective | 3.78 | 3.71 | 4.29 | 4.30 | |||||||

*Less than 5%

**Less than 1%

In Canada, too, differences due to location could be seen in the assessment of players in governance. Three types of player stand out when the more agricultural sites are compared with the economically diversified sites. In agricultural sites the assessment of the effectiveness of elected federal representatives was higher than in the diversified sites. On the other hand, in diversified sites the assessment of municipal councillors and community or voluntary groups was higher than in the predominantly agricultural sites. The agricultural economy in both countries has always been dependent on representation by their elected representatives to higher levels of government to obtain income transfers and privileged entitlements such as supply management and price supports to address economic hardship. Economically diversified economies are not so dependent on entitlements, but rely on good roads, local public services and favourable tax rates.

The Canadian results also mean it is necessary to be aware of the differences between provinces. For four of the six types of players in governance, respondents in Ontario rated their elected provincial representatives and elected federal representatives more effective than did their Quebec counterparts. In contrast to Ontario, the Quebec respondents gave higher ratings to their municipal councilors and local business leaders, that is to say those governing players closer at hand. This result may be interpreted as a reflection of the different policy approaches to regional development between Ontario and Quebec and the municipal government reforms in Québec, which happened earlier and with much more local consultation than in Ontario.

Male and female perceptions of effectiveness were similar for all players in Canada, whereas in Japan a gender pattern emerged for four of the six types of players in governance. The players for which there were differences in Japan are mayor, municipal councillors, local business leaders and elected prefectural representatives. For all four the test statistic was positive indicating that males gave higher ratings than females. This pattern of response was not really seen in Canada and could be attributed to the fact that males continue to dominate in rural Japan.

Finally, the differences between Japan and Canada in the patterns of response according to place of birth could be clearly seen. There were no differences in perceived effectiveness of governance players at all due to place of birth in Japan, whereas in Canada there were significant differences for three of the six types of player. In particular, significant differences were seen with respect to the perceived effectiveness of municipal councillors, elected provincial representatives and elected federal representatives. The average scores for each of these players mean that those born in the community scored these players higher than did respondents born outside the community. This pattern could be understood, if the newcomers were minorities with needs and perhaps core values that are not being well represented by elected officials who were perhaps nominated by entrenched constituency organizations or from the population born in the community. The importance of this result for revitalization lies in the high proportion of newcomers in three of the four Canadian sites. In one site, Tweed, newcomers are in a majority, making up as high as 80% of the population. Yet they do not feel that their interests are being effectively represented at any level of government.

Desire to remain in and revitalize a community

One of the necessary conditions for successful rural revitalization is people’s desire to take action. The household survey asked people’s feeling about living in their community as follows: ‘If I can, I will remain a resident of my community for a number of years’. The premise is that people who want to remain in their community contribute more to revitalizing that community than do those who do not want to remain. The number of people who want to remain is a principal factor for rural revitalization.

We explore the hypothesis that rural people in Canada mainly choose where they live while people in rural Japan are mainly constrained to live in their community as their fate. In the 1950s the proportion of farm households relative to total rural households in rural Japan was more than 90%. Today the proportion is much lower though many rural households have their roots in farming.

Family succession remains strongly influenced by a sense of responsibility to transfer their heritage to future generations forever. This situation is a kind of fate. Marriage is a free choice today in Japan, but living in a community is not as free a choice for the couple. Either the husband or the wife often becomes a resident member of a family deeply rooted in a community. The majority of incoming spouses are female. The household survey attempted to discover evidence of the extent to which people from these households want to stay in the community for a long time. The results reveal interesting characteristics of the Canadian and Japanese sites as shown in Table 6.

The desire to remain in a community is much stronger in the four Canadian rural sites than in the two rural Japanese sites with about 20-30% points more agreement among Canadian respondents who do want to continue to live in their community over the long term. This evidence supports the conclusion that communities influenced by circumstantial fate seem to have lower commitment within households to remain in the community long term. On the other hand, the proportion of people who do not want to stay long term is under 10% in the two Japanese rural communities, which some would say have been strongly influenced by fate.

Table 6. Will to remain in a community in selected Canadian and Japanese communities; numbers of responses and percent distribution, 2001

| Canada | Japan | |||||||

| Ste Françoise | St-Damase | Tweed | Usborne | Iitate | Awano | |||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |||||

| Disagree Neutral Agree |

3 |

10 |

5 |

4 |

8 |

6 |

6 |

10 |

| Total responses | 87 |

128 |

94 |

94 |

99 |

82 |

94 |

84 |

| Disagree (%) Neutral (%) Agree (%) |

3.4 |

7.8 |

5.3 |

4.3 |

8.1 |

7.3 |

6.4 |

11.9 |

| Total (%) | 100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Source. NRE Household survey, 2001

Note 1. ‘Disagree’ groups the respondents in the ‘Strongly disagree’ and ‘Disagree’ categories.

2. ‘Agree’ consists of the respondents in the ‘Strongly agree’ and ‘Agree’ categories.

3. The total numbers of respondents are less than the totals in Table 1 because every respondent did not answer the question reported in Table 6.

Very few respondents in either country do not want to stay for the long term, 3.4-7.8% in Canada and 7.7-9.0% in Japan. These numbers are small proportionately and therefore not likely an impediment to revitalization. However, when added to the significant proportion of undecided or neutral responses from the Japanese households, the total is not an encouraging sign of long term commitment. The total accounts for more than a third of the sample in each Japanese site, about 21-32% of the respondents. Recall from Table 4 that respondents under 50 years of age on average do not agree that their opinions are respected, scoring only 3.09. If our premise is correct, these results suggest that depopulation will continue for some time, reducing the effectiveness of rural revitalization initiatives to improve the demographics in the two sites in Japan. In particular if revitalization is equated to demographic stability, political leadership may expect to lose public confidence in its effectiveness.

The evidence is more favourable in terms of potential commitment to engaging households in revitalization in the four Canadian sites. For example, 84 of the 94 households surveyed in Usborne declared that they want to continue living there for the long future. Even in more remote Ste Françoise, 74 of the 87 households surveyed are there for the long term, all things being equal. This preference may have a lot to do with lifestyle, age and desire for personal freedom within households associated with choice as opposed to fate. Revitalization strategy in the Canadian sites could target these qualities, especially with respect to governance and the design of economic initiatives that reinforce lifestyle and preserve rural amenities.

The third observation is that male and female respondents in the two rural sites of Japan have similar patterns of agreement about wanting to live in their community for the long term. This pattern is evident in spite of the fact that one spouse is often from outside the community. The result is further evidence that newcomers to the Japan sites have been assimilated. Furthermore, assimilation seems to apply equally to male and females, despite the expectation that male spouses born elsewhere will bring a new sense of feeling to a community. However, one may not assume that assimilation translates into strong commitment to place, given the proportion of noncommittal answers among the Japanese respondents.

Conclusion

Three patterns in the data dominate all others. First is the low assessment of communities and of the effectiveness of players in the governance of rural places by the young under 50 adults and by females. The younger end of this group and women generally have limited assertiveness and power in rural cultures. The second uniquely Canadian pattern is that respondents born in their communities do not have the same perceptions as respondents not born in the communities. The two groups do not agree on almost any attribute of their community, even though newcomers were generally a strong majority at the time of the survey. The third pattern is the strong indication for presence of social capital and social cohesiveness in Iitate at the same time as the Iitate economy has been in serious decline, that is to say, not revitalizing.

The first pattern of low assessments by females is primarily a feature of the two Japanese sites. The lower opinion about their communities by younger adults under 50 is a more serious concern for revitalization. Their perceptions, like those of the newcomers, are in disagreement with the over 50 adults and people born in their communities. This divergence of views may signal that the true reality is weak social capital and social cohesion. At the same time in the Japanese sites, the higher income households seem to make use of bridging social capital in forging relationships beyond their community.

The assessment of each community in Canada clearly varied depending on whether or not the respondent was born in the community. There can be no effective voice for the needs, vision and choice of instruments for revitalization without agreement between the two parts of the Canadian site populations. The prospect for a workable revitalization strategy, willingly accepted to the degree necessary to bring forth investments at the household and community levels seems remote. The evidence shows that each site has two populations with significantly different perceptions of valued attributes. Half the governance players, municipal councillors, the business community and Members of Parliament are rated effective by people born in the place and not effective by people born elsewhere. The road to revitalization seems even steeper if these differences reflect a sense of privileged entitlement on the part of those born in the place that seems to exclude the needs and values of the rest of the population.

The agreement on perceptions between newcomers and born-in-place households for the two Japanese sites also raises opportunities for revitalization. The newcomers are apparently not challenging established perceptions. Therefore rather than acting as a force to revitalize social capital, newcomers help sustain the existing models. An argument could be made for the need to correct the tendency to conform by newcomers to the Japanese sites, as a necessary part of a complete revitalization strategy.

The last conclusion is drawn from the contradiction between the positive patterns of perceptions for Iitate and the evidence of ongoing and serious devitalization. Overall, Iitate is perceived by its households as progressive with strong indicators of internal cohesion and social capital. The village has almost 15 years of progressive leadership on engaging women and youth in development and offsetting the isolation from the mainstream cultural life of Japanese. The village has a strong enough self-identity to vote against amalgamation with its neighbouring coastal municipalities, yet none of this has slowed out-migration, disaffection of youth, disinvestment and worsening employment prospects. The evidence on willingness to live in a community for a long time supports this conclusion. Only 68% of males and 66% of female respondents in Iitate said that they want to live there over the long term, despite all the local municipal and prefectural efforts over the past fifteen years. The high rate of net out-migration since 1990 fits the survey evidence well though respondents are very satisfied with the effectiveness of municipal efforts at revitalization. This conclusion suggests that revitalization efforts may have been trumped not only by larger economic forces, but also by the fact that a large minority of the population does not want to stay in Iitate and therefore cannot be successfully mobilized to take personal action at the household level to help revitalize their community.